| Home Page

Photo Page

Contact Page

Guest Book Page

Photo2 Page

Photo3 Page

Photo4 Page

Photo5 Page

Whats New Page

Custom Page

Favorite Links Page

Photo6 Page

About Page

Custom2 Page

|

A QUICK TRIP BACK IN TIME TO SEE HOW/WHY/WHEN FILMS AND MUSIC BECAME INTERTWINED

Many theories abound as to why music was introduced to the silent film..........Composer Hans Eisler, in his book "Composing For the Films" suggests the assumption that silent films must have had a "ghostly effect" on their viewers - the pure cinema must have had a ghostly effect like that of shdow play (see "Magic Lantern" details on this website).The magic function os fmusic.consisted in appeasing the evil spirits unconciouscly dreaded. Music was introduced as a kind of antidote against the picture......The images of real, living people were shown - who were at the same time silent - living, yet non-living, ie scary!......Interesting!

On the other hand, Kurt London, in his early study "Film Music" suggests that music was introduced to drown out the noise of the film projectors of the early days: he points out that inadequate accoustics rather than "any artistic urge" was responsible for motion-picture music. But - as Eisler points out - why should the noise of the projector be "so unpleaseant?" London observes "The reason which is aesthetically and psychologically most essential to explain the NEED of music as an accompaniment of the silent film, is, without doubt, the rhythm of the film as an art movement". It was the task of the musical accompaniment to give the film auditory accentuation and profundity.......Even more interesting.........!

The first known use of music with the cinema was on December 28th, 1895 (Stan was 5!) The Lumiere family first tested the commercial value of some of it's earliest films. That screening - with piano accompaniment - took place at the Grand Cafe, on Boulevard de Capucines in Paris. It is also believed that, at the first public showing of the Lumiere programme in Britain, at the Polytechnic on regent Street, a harmonium from the Polytechnic's chapel was used to accompany the showing. This british performance took place on February 20th, 1896, and by April that year, orchestras were accompanying films in several London theatres.

In those first commercial years, the musical material used consisted of just about anything that was available at the moment - and, more often than not, bore little dramatic relationship to what was happening on the screen. Musical selections ranged from light, cafe music to some of the serious classics but - in those early days - musicians professionalism left a lot to be desired! In many theatres, the orchestras would simply play through a certain number of compositions - and then simply get up and leave........! The producers of the films were far from happy with this situation, but there was little that they could do, since the exhibitor determined what role the music should play in its relationship to each film.

As cinema discovered its potentialities - becoming more and more popular - some of the more sensitive producers desired to provide a specific score for a specific picture. This idea first came into fruition in 1908. A Parisian company, Le Film d'Art, encouraged well-known actors to perform on film some of the most famous plays in the repetoire. The Comedie Francais and the Acadmeie Francais lent support to the idea - and the group put on their first production - "L'Assassinat du Duc de Guise". The most significant fact was that the famed french composer, Camille Saint-Saens was wasked to compose a score SPECIFICALLY for this film. Saint-Saens readily accepted and later developed his muic for the film into a concert piece, naming it "Opus 128" for strings, piano and harmonium.

However, probably mainly because of the expense, the idea did not catch on - but there grew an industry that answered the ever-growing need for music to accompany films.

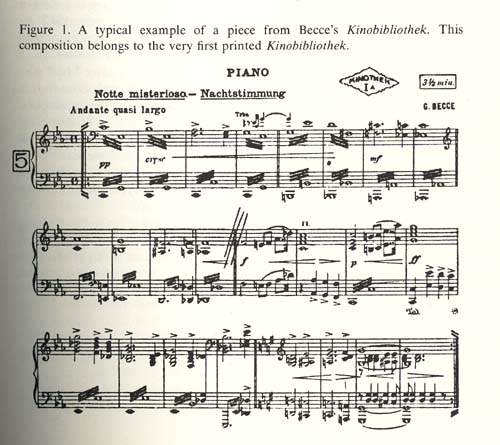

In 1909, the Edison film company began issuing "specific suggestions for music" for the films they produced. By 1913, theatre orchestras and pianists were able to acquire music for specific moods or dramatic situations- all conveniently catalogued by the publisher.......The most famous example of this concept was Guiseppe Becce's KINOBIBLIOTHEK (or KINOTHEK, as it was called (see picture opposite) first published in Berlin in 1919. The Sam Fox Moving Picture Music Volumes, by J.S. Zamecnik appeared as early as 1913 But it was Becce's KINOTHEK that was best known. |

|

|

EXPLAINING THE KINOTHEK........

In the KINOTHEK were many pieces of descriptive music, classified according to style and mood; many of the pieces were specifically composed by Becce himself. This system of cataloguing tended towards pigeonholing, eg:

DRAMATIC EXPRESSION (Main Concept)

1. Climax; (subordinate concept)

(a) Catastrophe (sub-divisions)

(b) Highly Dramatic - agiato

(c) Solemn Atmosphere; mysteriousness of nature.

2. Tension - Mysterioso

(a) Night; sinister mood;

(b) Night; threatening mood;

(c) Uncanny - agiato

(d) Magic - apparition

(e) Impending doom "something is going to happen....."

3. Tension - Agiato

(a) Pursuit, flight, hurry;

(b) Flight

(c) Heroic comabt;

(d) Battle

(e) Disturbance, unrest, terror;

(f) Disturbed masses, tumult;

(g) Disturbed nature: storm, fire.

4. Climax - Appassionato

(a) Despair

(b) Passionate lament

(c) Passionate excitement

(d) Jubilant

(e) Victorious

(f) Bacchantic (Orgiastic).

WHAT HAPPENED TO MUSIC AND SILENT FILMS IN THE UNITED STATES?

In the USA, it is generally acknowledged that one MAX WINKLER was the first to catalogue music for the silent film. Winkler was a clerk in the Carl Fischer store in New York. During 1912, the demands on the Carl Fischer music store for music to accompany films became so great that Winkler began losing sleep over the matter. "FILMS IN REVIEW": (Max Winkler interview) "One day, after I had gone home from work I could not fall asleep. The hundreds and thousands of titles, the MOUNTAINS of music that Fischers has stored and catalogued kept going through my mind! There was music - surely to fit ANY given situation in ANY picture - if we could only think of a way to let all these orchestra leaders, pianists and organists know what we had! If we could use our knowledge and experience not when it was too late, but much EARLIER, before they ever had to sit down and play, we would be able to sell them music - not by the film! Not by the ton.......! But by the TRAINLOAD!!

That thought suddenly electrified me. it was not a problem of getting the music. We HAD the music.....It was a problem of promoting - timing - and organisation. I pulled back the blanket, turned on the light and went over to my table. I took a sheet of paper and began writing feverishly. Here is what I wrote:

MUSIC CUE SHEET for "THE MAGIC VALLEY". Selected and compiled by M. Winkler.

Cue:

1. Opening - play Minuet No. 2 in G by Beethoven for ninety seconds until title on screen "Follow me dear".

2. Play -"Dramatic Andante" by Velvy for two minutes and ten seconds. Note: Play soft during scene where Mother enters. Play Cue No. 2 until scene "Hero leaving room".

Play - "Love Theme" by Lorenzo - for one minute and twenty seconds. Note: Play soft and slow during conversations until title on screen "There they go".

4. Play - "Stampede" by Simon for fifty-five seconds. Note: Play fast and decrease speed of gallop in accordance with action on the screen". (Interview ends)

"The Masgic Valley" was an imaginary film - but it made Winkler's point! Winkler wrote to the New York office of UNIVERSAL (there they are again!) FILM COMPANY and explained that if they would allow him to view their films BEFORE they were released, he could make up similar cue sheets for ALL of their films. This advanced preparation would give local theatres time to prepare adequate musical accompaniment for their films.

Paul Gulick, the then Publicity Director of UNIVERSAL liked the idea - and arranged for Winkler to view some films and make out cue sheets. Gulick was impressed by the result! Winkler was immediately engaged by the UNIVERSAL FILM COMPANY to provide musical cues for all of their films. The response of the theatre musicians, Winkler later recalld "was overwhelming. Everybody was delighted!"

Winkler left Fischers and formed a partnership with one of his (inevitable) early imitators, S.M. Berg.

As the demand on Winkler's music service grew he had a problem with supplying the theatre musicians with enough material to crisis proprtion. Winkler recalls: "In desperation - we turned to crime! We began to dismember the great masters. We began to murder ther works of Beethoven, Mozart, Greig, Bach, Verdi, Bizet, Tchaikovsky and Wagner - everything that wasn't protected by copyright from our pilfering. The immortal chorales of Bach became an "Adagio Lamentoso" for sad scenes. Extracts from great symphonies and operas were hacked down to emerge as "Sinister Mysterio" by Beethoven or "Weird Moderato" by Tchaikovsky. Wagner and Mendelssohn's wedding marches were used for marriages, fight scenes between husband and wife and divorce scenes: we just had them played out of tune, a treatment known within the profession as "souring up the aisle". If they were to be used for happy endings, we jazzed them up mercilessly. Finales from famous overtures, with the "William Tell" and "Orpheus" the favourites became galops. Meyerbeer's "Coronation March" was slowed down to a "Majestic Pomposo" to give proper background to the inhabitants of Sing Sing's deathhouse. The "Blue Danube" was watered down to a minuet by a cruel change of tempo."

As 'crime' never pays, Winkler's fortunes dwindled with the coming of talkies and he sold his entire stock of SEVENTY TONS of music to a paper mill for the meagre sum of ! Even then, before he could collect, the mill went bankrupt!

Theatre orchestras advanced to play all this music - one of the other problems was that the conductor would only have a small amount of time from the first viewing to the first performance. The general routine was that the Music Director (or Illustrator, as he was then called) looked carefully at the film to gain impressions of it's form and content. Then the film was shown again in sections so that he could calculate with a stop watch single scenes intended to be divided musically from each other. Next, he selected the music to be used, whether the score was to be a compilation of numbers (like the old operas) or more like Wagner's music dramas, using perhaps a psychological arrangements of the leitmotiv. Set numbers usually prevailed, with the occasional use of some main themes loosely related to the leitmotiv. Set number were placed at the climax of the film.

Conductors resorted to writing their own transitions from scene to scene - that was much easier. These own works appeared at first to be the least significant element, but they were probably the biggest proportion of a film, with the greatest value. London points out " they were created with feelings inspired by the film; compilations were, at best, only substitutes".

Rising from all this were great composers for silent films such as Sergei Eisentein - he composed for "The Battleship Potemkin" and "October" (recently discovered in the Einstein Archives in Leningrad). Such music made history.........

For small theatres that could not provide an orchestra, there were machines that could be purchased instead and these began appearing around 1910 and carried such names as "One Man Motion Picture Orchestra", "Film Player", Movieodeon" or "Pipe -Organ Orchestra". They could also supply a battery of sound effects and ranged in size from essetially a player piano with small pecussion set up to elaborate instruments equalling a twenty-piece pit orchestra. The "Fotoplayer Style 50" was 21 feet long, 5 feet wide, and 5 feet, 2 inches tall and capable of recreating effects such as lowing cattle, drumming hooves (in assorted gaits), varities of klaxons. street traffic, crackling flames, breaking wood and branches, rifle, pistol and machine gun shots - even the sound of a French 75MM cannon! (bloody hell!) It must have taken a certain kind of genius to operate!

It is common to have staff musicians on hand to play for silent film stars when they had a difficult scene to do. D.W. Griffiths first did this in 1913 on his set of "Judith of Bethulia".

Finally..........if you have ever seen an original copy of Walt Disney's "Fantasia" (1938) you will notice the conductor, Leopold Stowkowski, in silhoutte conducting the orchestra standing up in front of the screen. At one point, this was the only way that the pace and tempo of his conducting could match the film being shown - and was a common occurrence at one point!

The above are extracts from "Film Music - A Neglected Art" by Roy M. Prendergast

Links to Other Sites

My Links |

|